Gwangju Biennale Premiers MaytoDay

30 October 2020Julia Bethwaite – The Scale, Politics and Political Economies of Contemporary Art Biennials (2018)

1 November 2020Interview with Gabriele Horn, Director of the Berlin Biennale

Interview recorded on October 27th 2020 and later transcribed for IBA.

Gabriele Horn – Director Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art – Photo: Karin Müller

IBA: Can you give us an account of what the situation is for your current project and how the covid19 crisis affected it?

Up until early march this year we were planning to open the 11th edition of the Berlin Biennale at the beginning of June and have it run till mid-September, following a timeline similar to our previous editions. As soon as news about the spread of the pandemic reached us and we realised we were headed to a lockdown situation it became clear that we could not have gone ahead as we planned. This was in the first half of March, so roughly 3 months before the opening which meant that we had already expanded our team to meet all the needs of the upcoming exhibition. As many other biennials with a small core team, we rely on these positions in the months leading up to the opening. Thankfully, after being forced to close both our office and our project space in the “Ex-Rotaprint” building in Wedding, we were able to adapt our operation to a home office and remote working situation. It took a little to adapt and getting used to the new situation, but everybody was very understanding at least. The big question which remained was how to manage the overall project under these new circumstances as, especially in the first weeks, there was no certainty at all about the possibility of having these kind of large event for quite a while. If we were to go ahead we were facing a backlash on two fronts: the availability of the venues we had planned to utilise and budgetary issues.

Regarding the funding our biggest concern was in regards to the support we receive from the Kulturstiftung des Bundes, a public federal body, which is always contingent to a two-year period. Delaying the opening of the exhibition meant missing this deadline while at the same time having to extend all contracts with collaborators, artists and curators. For a few weeks we really struggled with these aspects and had to resort to furloughs and other social measures to protect our employees.

Moreover all these efforts were dependent on us finding new dates and renegotiate the use of the venues we had planning to exhibit in.

The discussions with KW (Kunst-Werke Berlin) which has always been a venue of the biennial and is our long-term partner institution went very smoothly as there was a fundamental accord with the director, Krist Gruijthuijsen. They also needed to re-adapt their schedule but as everything was up in the air it was relatively simple to block a slot of time for the Biennale. The situation was much more complex with Gropiusbau as their calendar foresees a number of simultaneous shows which would require a lot more coordination. It took a lot of negotiating but eventually around mid-May it was clear that September would have been a possible new date. This was really the moment in which we realised that we could actually stage this 11th Berlin Biennial and that it would run from the beginning of September to the beginning of November, you can imagine our relief.

In regards to organisational questions we were also worried about the shipments, especially as at the very beginning of the lockdown it wasn’t clear at all how much the logistic industry would be affected and how much extra this would weight on our budget. Again in a lucky turn of events it was a relatively small issue, especially through the help of our cooperation partners throughout the world. The most complicated situation we faced in Brazil where we had to give up on two loans because not even the curators there were able to access the museum and its storage spaces.

Alongside all these pragmatic and practical issues there was also a human and more personal side we had to face. In the first period we held many intense talks with the curators about if and how to go ahead with the project. These were discussions overshadowed by our general feeling of shock for the developing situation here in Germany, as well as across Latin America, a continent hard hit by the pandemic and where most of our curators have their roots, families and where a number of invited artists are living. This goes beyond the professional limitations the pandemic posed to our project, it was just a very emotional and complicated period to navigate. In a way the fact that their curatorial project and research rotated around ideas of solidarity, vulnerability, exclusion, health care and so on, gave us a few extra tools to tackle the situation. Besides, it reinforced our belief about the validity of the exhibition in the new context. Corona became a magnifying glass, a lens through which we could re-interpret all the thoughts and arguments which the curators wanted to unfold in the exhibition.

Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende (MSSA), Installation view, 11th Berlin Biennale, Gropius Bau, 5.9. – 1.11.2020 – Photo: Mathias Völzke

IBA: Can you give us a sense of the discussions you mentioned with the curators about the situation and the consequent decisions you were facing of whether or not to do it and in what form?

It was a very special situation as we had to have these discussions during the lockdown phase with no real sense of when it would be over. This was very complicated to manage for all the reasons I have raised earlier, thankfully there was always a little light at the end of the tunnel with a sense that maybe in May or June things would start to ease. But still the question remained of whether we could do it in these circumstances, ethically before any logistical or budget thought. They were very frank discussions in which neither we as an institution nor the curators were pushing for things to happen that were not possible. There was a common understanding that we were and still are all in the same situation. I think we all tried to act according to the principles of solidarity, respect and shared decisions. We never really had a moment in which one side put down their foot to say, “we have to do it” or rather “we don’t want to do it”. And these discussions also slowly filtered through to the content itself and the exchange with the artists all over the world.

Curators of the 11th Berlin Biennale, from left to right: Renata Cervetto, Agustín Pérez Rubio, María Berríos, Lisette Lagnado – Photo: F. Anthea Schaap

IBA: In your “press video” you mentioned something which I think is quite important and relevant not just for this but maybe also for coming biennials generally when you say that this was an “unlearning” experience?

If I think back to that statement what was really important to me was to transmit a sense that we all need, as a society first of all, to go through this process of unlearning in relation to the norms and values we considered normal. We have all been confronted with the limitation in travelling, we had to change our ways of gathering and sharing, of caring for each other. And we also started questioning whether a biennial has to necessarily buy into the neo-liberal logic of being always larger event and generally “more” than the previous one. I think what is important is to reflect collectively on how it is possible to root our content, our creative and artistic expression to our context. How can we find a way to relate more to the context in which we are anyhow producing our exhibitions, is the question I had in mind. We really need to use this time wisely for these thoughts because otherwise we will end up with a “business as usual” situation once the corona emergency is over, if it will ever be the case.

Delaine Le Bas, St Sara Kali George, 2020

Mixed media

Installation view, 11th Berlin Biennale, daadgalerie, 5.9.–1.11.2020

Courtesy Delaine Le Bas; Yamamoto Keiko Rochaix, London – Photo: Silke Briel

IBA: It seems obvious maybe but one of the aspects that certainly had to change and be re-thought was the opening, can you tell us a little about both challenges but hopefully also opportunities that an opening which was not an “event” as it is usual offered to you?

Maybe let’s start with the positive aspects, not just about the episodic but more generally about being able to present the works during these times. First of all, there was a sense of duty we had generated from the solidarity and support to the artists, that had already been invited and worked on new productions for the Biennial. In order to maintain their contract and therefore also guarantee their fees and production costs we needed to stage the event, due to the funding structure of a biennial like any other art institution we were able to do so only if the exhibition took place. In times like these of extreme vulnerability for the artists and the cultural sector overall, this was an extremely important point for us. The other positive aspect of having a “soft opening”, let’s call it, was that people had much more time to engage with the works this was valid for the public of course but also for the press preview, which we also had to limit and spread over time. Again, practically speaking, we had to come up for the first time with a system based on time-slots for our visitors, to be able to control the amount of visitors present at any time in our venues.

I think the response we got, our time-slots for the first two days were completely booked in a day or so, is a clear sign of how much the audience was longing for culture, for contemporary productions again and for us personally it was incredibly moving to receive a lot of positive remarks on our choice of opening regardless of the circumstances. There are two aspects that really make me happy in this sense, first of all that we managed, to have at least a small event for the artists who could be present the day before the press preview safely in the yard of KW, this gave us at least a taste of normality and that actually, the timed entrances gave visitors and press a lot more time to engage with the works than usually happens during openings.

Clearly there were drawbacks too. We could not have the usual 8.000 people strolling between venues and creating that festive atmosphere of encounter and exchange between the public and the artists that usually takes place. But this void was at least partially filled through the many expression of solidarity and support we received not only in person by those that despite everything could be present but also digitally through social media, email and all other forms.

Andrés Pereira Paz, EGO FVLCIO COLLVMNAS EIVS [I FORTIFY YOUR COLUMNS], 2020

Mixed media

Installation view, 11th Berlin Biennale, Gropius Bau, 5.9.–1.11.2020

Courtesy Andrés Pereira Paz; Crisis Galería, Lima; Galería Isla Flotante, Buenos Aires – Photo: Mathias Völzke

IBA: Did the situation impact the way you chose to work with the artists (travel limitation etc) and give us a sense of how you developed a new approach?

I want to go to a specific example to answer this question because I think it exemplifies what happened very well. We were working with the teatro da vertigem, a performance and theater group based in Sao Paulo, Brazil and originally, we had planned to invite them to Berlin and plan something for the public space here. We had already defined a concept and had started to plan all the practical aspects of this. Once the pandemic hit it was clear that it was not going to be possible to realise anything in the public space and even more so for them to even come to Berlin was going to be near impossible. They were very quick to react to the situation however and started re-thinking their intervention, modifying certain aspects of course but keeping most of it as it had been planned for Berlin but to be staged instead in Brazil. To describe the work to you briefly, Teatro da Vertigem blocked for one day the Avenida Paulista in Sao Paulo and had approximately 120 cars travelling backwards. Now to give you a sense of scale of this action, for those who are not familiar with the city this six lane road really is the centre and heart of the city, so we had to do a lot of institutional work to help them gather all the permissions and so on to allow this project to take place, aside of the financial support needed. I believe it turned out to be a very strong work especially in light of both the political, social and health situation in Brazil. While sad that we could not realise it here in Germany we still wanted to give it the attention it needed and placed the documentation of it in the opening rooms here in KW.

This just to give you an example, there are of course quite a few other works that were affected in their production by the situation. In some cases this was clear to see for the audience while in others it was much more subtle depending also on the media and type of work but I am very happy to say that despite everything all the works which had been planned as new production managed to be delivered.

Małgorzata Mirga-Tas, Lost Memory, 2018

Wax

Installation view, 11th Berlin Biennale, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, 5.9.–1.11.2020

Courtesy Małgorzata Mirga-Tas – Photo: Silke Briel

IBA: As an institution that interacts more than others with the wider urban fabric do you feel this can also be a moment to re-think a “neighbourhood” relationship with the audience?

Certainly, as Berlin Biennial we had already gone in this direction regardless of Corona with the opening of the “Ex-Rotaprint” space in Wedding last September. The idea was that, as I have always believed, that the Biennial should be more rooted again in the city of Berlin. This had been the case in the past of course, just think of the first Berlin Biennial in 1998 which really was to showcase the emerging artist scene in the city. Over the years we have increasingly become more international, more interacting and engaging with the topics and artists from across the world. This raised a lot of complaints by locally based artists that it was a stage they were excluded from. I had this dream for a while to open a sort of project space for the biennial to act as an encounter space but also as a space to start unfolding the topics which are being explored in each upcoming edition. And of course such space would also serve as a base for our regular outreach work in the neighbourhood.

Now specific about the corona situation of course we are forced to depend more on our local audience than we were already simply because there is an impossibility for oversea guests to even come to Berlin.

exp. 3: Affect Archives. Sinthujan Varatharajah – Osías Yanov, 11th Berlin Biennale c/o ExRotaprint, 22.2.–2.5.2020, extended until 25.7.2020

Installation view – Photo: Mathias Völzke

IBA: Does this also change the feeling of the biennial?

I think and hope that this is just a different way to relate to our audience and as I mentioned our local artists. It was and is about finding a new way to interact and stimulate also local discourses, maybe also because the Berlin art scene has since become much more international itself it would feel wrong if this would actually change the face of the Biennial all together. It is also true that due to Corona we had to change our public presence a lot in this edition, so also the space was used only until beginning of March. We then had to shift to digital with meetings, conferences and publications that were distributed through these means. Maybe this is something which will unfold more during the next editions…

Pedro Moraleida Bernardes, Young-jun Tak, Florencia Rodriguez Giles, Installation view, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, 5.9.–1.11.2020 – Photo: Silke Briel

IBA: Can you give us an example/idea about how the IBA network represents a resource in these circumstances?

I see the IBA as a platform for exchange primarily, exchange of knowledge, exchange of experiences and consequently as a space that allows us to come together to face the different contexts biennials are working in. This idea of exchange is of course also linked to an idea of solidarity in this sense. To stay true to these values I even thought whether our resources are better spent to organise a big conference or rather used to foster these cases of solidarity through exchange and discussion of how to deal with the challenges we face and will face in the future. It is more relevant than ever to have a collective discussion between us about these challenges that go from financial cuts to the complexities of staging an event as we all faced this year, not just for biennials but making our voice heard for the protection of cultural structures generally as we are all facing a very difficult moment. This of course means to become more active at a political level in the future and remains something we need to discuss between us.

I think this thought is a direct consequence of witnessing the reaction of the government here in Germany which admittedly did a lot and very quickly to support the cultural sector, and yet, even in these conditions it became obvious that it was not enough.

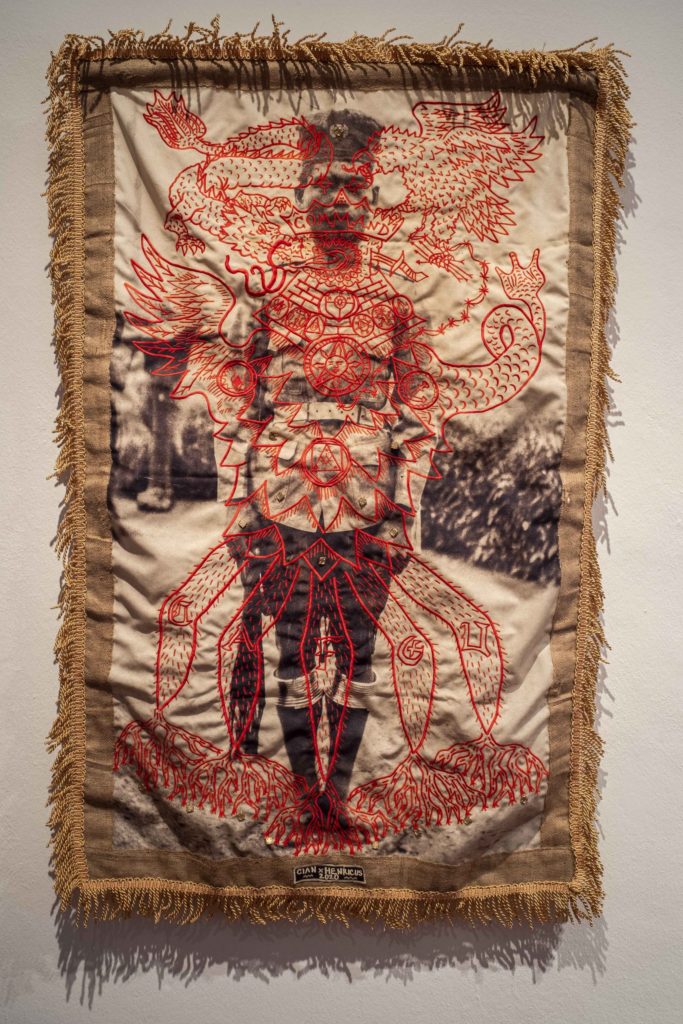

Cian Dayrit, Installation view, 11th Berlin Biennale, Gropius Bau, 5.9.–1.11.2020 – Photo: Mathias Völzke